Negotiation 2022-6-13

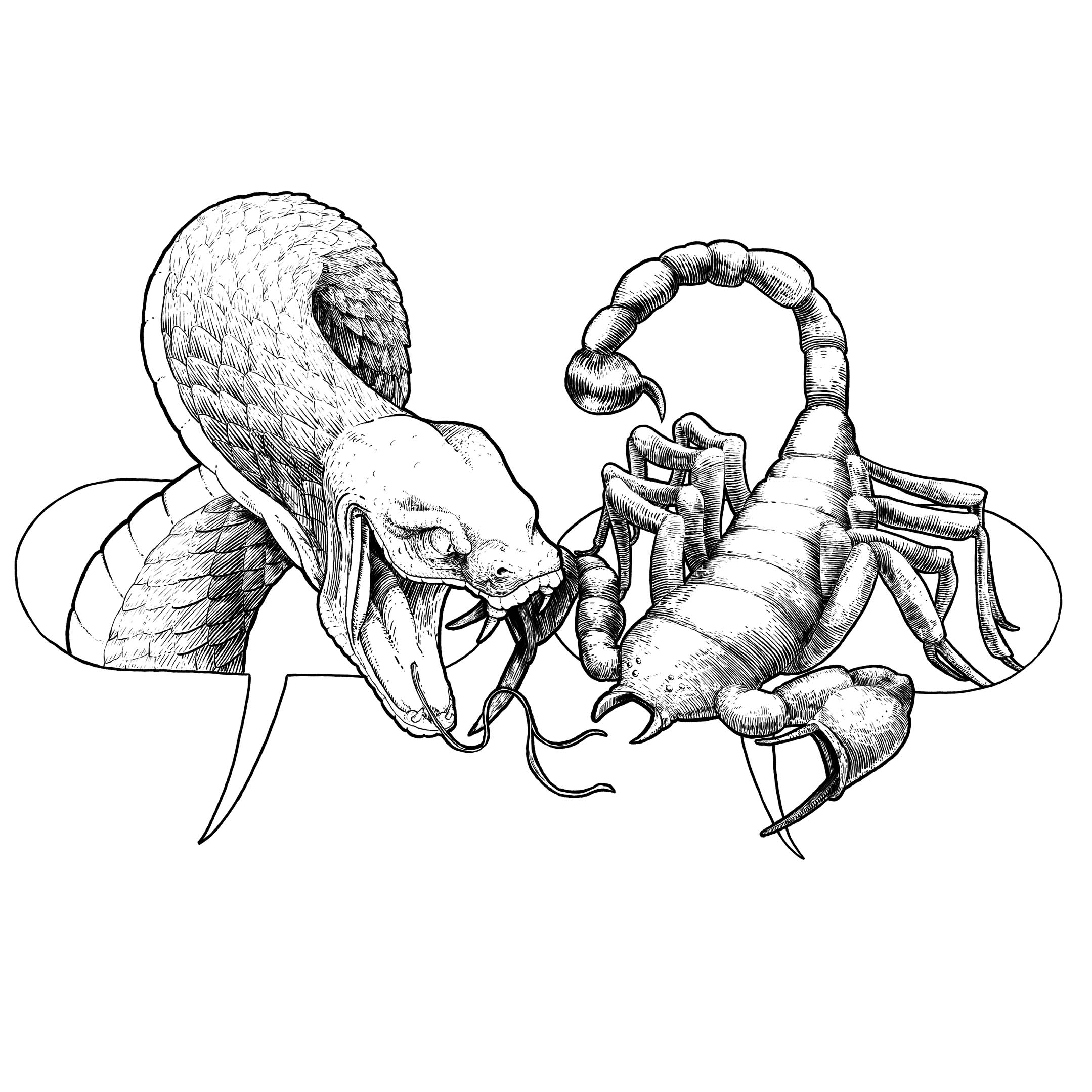

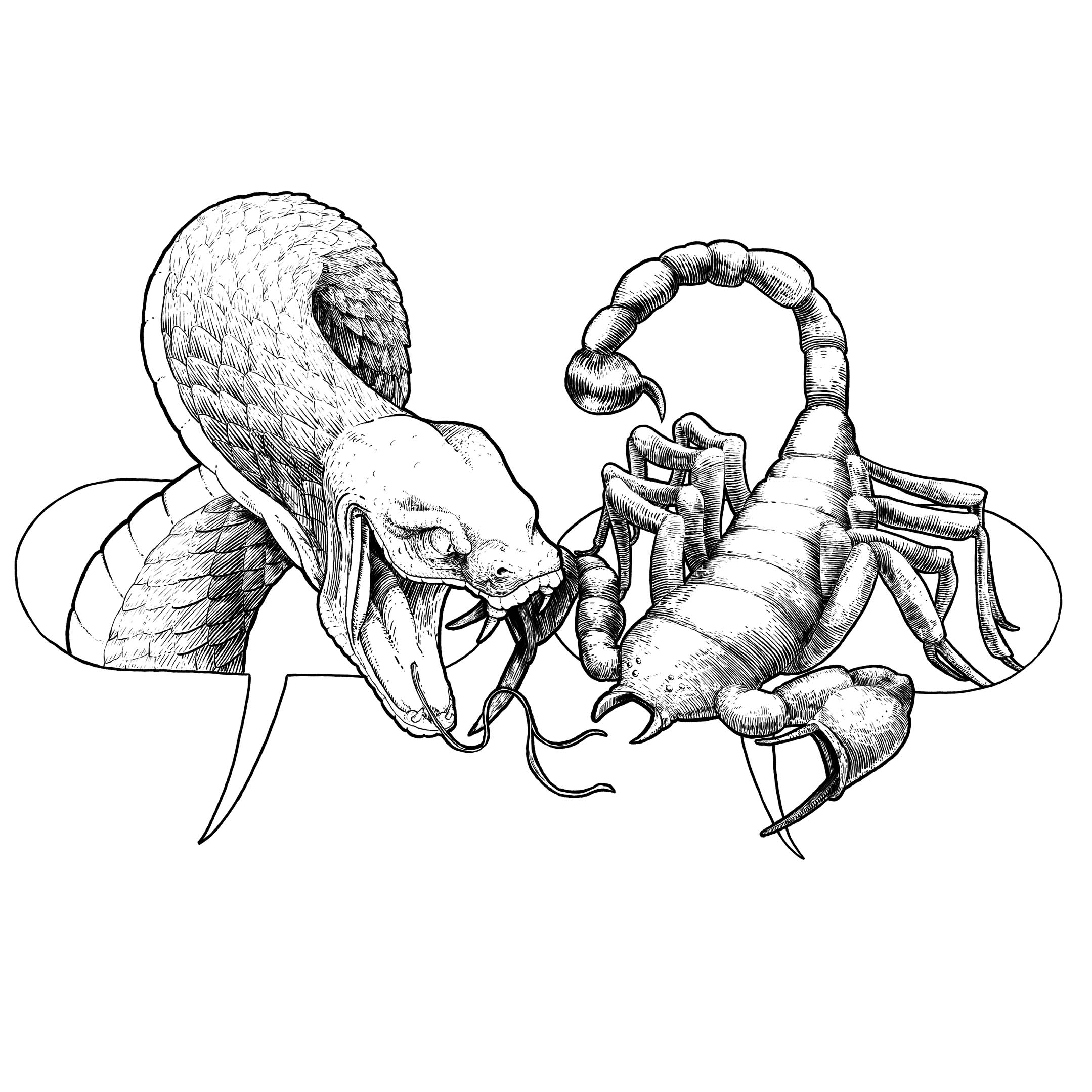

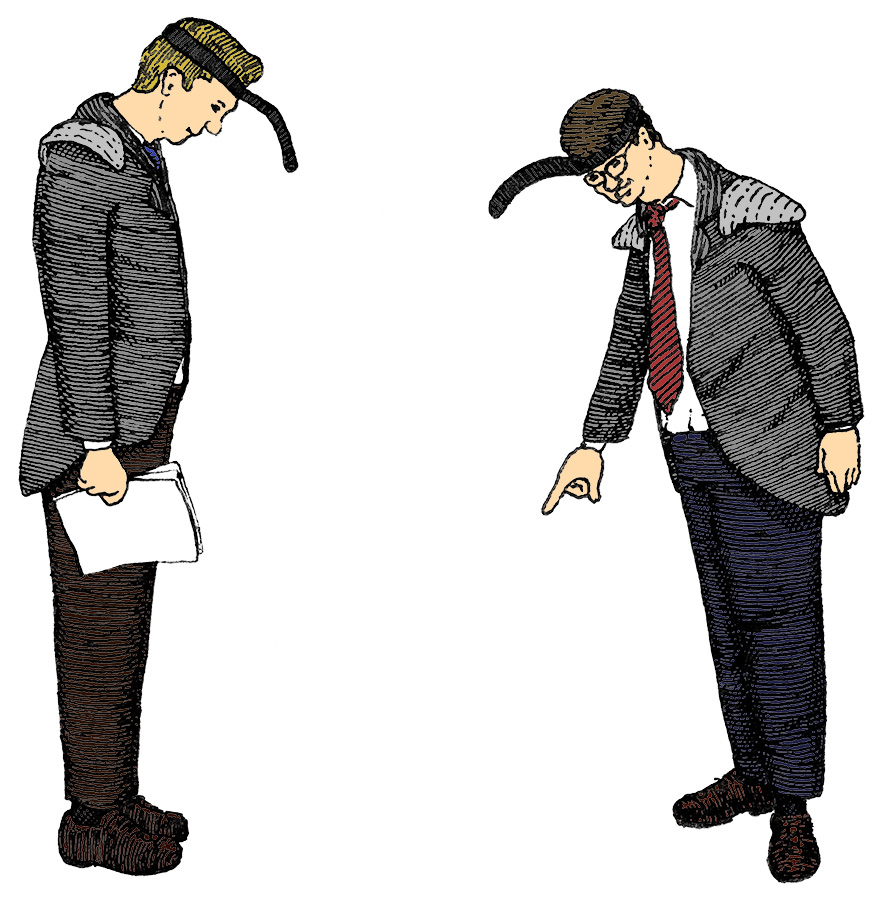

I made the pencil drawing for this a couple of years back. I like to think this digitally inked version has the impact and immediacy that the original seemed to lack.

They built the school long before most of these housing developments. I assume that's why it sits on such a big lot, with the actual building more than a football field's length from the road. They'd cut the grass within days of my walk and left the clippings in browning, broken rows.

What first distinguished the animal in the distance from one of these clumpy rows was its pointed ears and bouncing gait. Some kind of canine.

While I watched it from the road, a woman slowly walking along the driveway toward the school watched it from her closer perspective. I was on a mission to get nowhere in particular, so I eventually caught up with her.

"Did you see that canine?" I asked, taking a wide path around to keep my distance.

Startled, she looked up from her phone but then smiled. "Yeah. I think it's a mangy fox. I thought you might have been the fox."

"Ah. Yeah, they get pretty rough-lookin' out here sometimes." I'd never seen one out there. "Have a nice day."

"Thanks. You too!"

I continued on the long sidewalk through the schoolyard to the old suburban development behind it and walked on. I don't remember where to.

Alright what'd I miss? See, I've returned to college to finally try and beat myself into becoming some kind of scientist or something. It's been going well. They told me it would if I went back with the intention of actually learning stuff instead of just doing it because it's what everyone told me to do.

There are some birds in the back yard who are mostly gray with a spot of black on the very tops of their heads that look like little beanies. Apparently they're called "cat birds"? I call them the gray birds with the beanies.

There was a bird who looked kind of like this, but without the beanie, in the college parking lot. He was pecking at a mostly hollowed out berry or nut or something, trying to get the perfect angle on it. As if this wasn't enough of a challenge, he was insistent on periodically emitting a single tweet every five to seven seconds. If the time came while he held the thing in his beak, the tweet would come out muffled, like it does when you try to talk while holding your calabash smoking pipe in your mouth.

In clean-rooms and PC cases, people who sound like they know what they're talking about tell you to keep more air moving in than out to prevent dust buildup.

I just finished reading Philip K. Dick's The Crack In Space. He wrote a lot of wild, philosophical, "genre-defying"--the quotes are to indicate that I'm rolling my eyes at myself--stories. He also wrote a lot of stories to pay the bills. The Crack In Space seems more like one of those. That's not meant disparagingly.

Even though it lacks the meditative tangents and perspective-bending shifts that made him a posthumous sci-fi prophet, the man couldn't help but touch on ideas that you probably haven't thought of before. He does that here in an interesting book that doesn't require the dedication of an apostle to keep up with and have fun reading.

The profile was recognizable, even through the windshield of my car about 50 feet away. From a perfect dome stretched the leathery neck that held up this little head, regarding its absurd situation in the middle of a long driveway through the woods.

I slowed and swung wide around the dark reptile to alert the driver behind me. He followed suit. He's a coworker I've come to like and with whom I apparently share a morning schedule.

The farthest parking spot from the door was the nearest to the turtle. I checked my hands for cuts as I walked across what must have seemed a hard, vast expanse. I remembered the nitrile gloves in my car but not why they were there. Maybe I thought I'd encounter a turtle. I went back and put them on before attempting my approach again.

I've seen snapping turtles stretch their necks out farther than you might expect. This was no snapping turtle, probably what they call a box turtle. For safety's, sake I approached from behind.

Its shell scraped the asphalt as it gave a few four-legged thrusts with surprising speed. I reached down and it changed tack, withdrawing its limbs and head.

With both gloved hands I gripped the sides of this shell. It let out a sound that from a person might be called a resigned or annoyed sigh through the nose. Maybe it was hissing. Maybe it really was a resigned sigh. Maybe it had allergies like me.

I couldn't resist a quick peek at the face. A latticework of vivid orange ran around a reptilian grin and eyes that looked strangely meditative, even through the nictitating membranes that slid up to ease the glare of a furless primate's grinning face.

My peek was cut short by the feeling that I was intruding, so I turned my attention toward the edge of the woods that appeared to be the turtle's destination. A little beyond the gravel was a patch of moss by some tall grass. Maybe that subtle part in the grass marked a turtle trail. I sat it there and walked back, rolling my gloves into an inside-out ball as I removed them, the way they'd shown us in EMT school.

"You save a turtle today?" my workmate called as he got his lunch or whatever out of his car.

"Yep." I tried to say this the way a real man might say it, not someone who would regard seeing a turtle up close as the highlight of his week.

"Good deed for the day!"

Who knows what the turtle made of all this.

I heard somewhere that the flashes and fuzz you see when you get up from sleep in the middle of the night are caused by the fluid inside of your eyeballs drifting down off of the retinas.

A caller to a local radio station that was talking about ghosts said she experienced something like this. She said it looked like thousands of ants crawling around on the ceiling. She must not have heard the thing about the eyeball fluid, so she thought it was ghosts. It's funny she didn't think it was thousands of ants crawling around on the ceiling.

If you go walking in one of these suburban neighborhoods at night, you'll hear frogs chirping in the grass by the sidewalk.

I often try to find them, but mainly just to be a good sport. I never do. I know I'm close when they stop chirping, but no matter how close I get my face to the grass in my neighbor's front lawn, I never see them before I get embarrassed and move along.

The tiny frog's greatest advantage against big human faces is humans' natural aversion to looking weird in their neighbors' front lawns.

Tough family circumstances required the meager assistance I was able to provide, so I moved back home two years ago and have been here since.

I went to high school in this town and have memories all over it, but the places where those memories took place are occupied by strangers now. I'm a stranger here now too.

But if you've got a good bike there's good bike riding to be had. The generally well-intentioned board-of-chosen-municipal-something-or-others maintains a good path that connects to the next town, where the State maintains a wildlife management area with wide trails. The sealed-off, hamster-ball culture of the area that makes sure Mainstreet stays dead also keeps crowds small on these miraculously maintained trails outside of hunting season.

If you're not into driving, hunting, or driving to go hunting, you have to find your own fun in a town like this. It's alright.

Reading the Jul. 1981 issue of Asimov's Science Fiction Magazine. It's never just fiction in these. Right now I'm in the middle of some guy's massive scree about dragons.

It's not as good as the 1968 Analog I'd picked up at the same time. I blame Asimov himself. That's the trouble with slapping your name on stuff like that.

I had missed the big haul of old sci-fi mags that the book store had posted about on Instagram the week before and was picking through what was left. A collector must have bought most of the lot. I just like reading the damn things.

It's alright. I was bummed when the used book stall in my town's farmer's market closed. I still am, but this place has so much more. I was used to browsing a skinny shelf on the outskirts of a small library of mostly romance books -- which is all well and good -- but this place has half a room of sci-fi. The very good stuff. Found more John Barnes. Philip K. Dick. William Gibson.

I haven't spoken to the guy who owns the place but I'd like to. He offers the charm I'm always been after. On a shelf in the sci-fi room there's a stack of small sci-fi prints. They look like cover illustrations. The lady working the counter that day wasn't sure what they were or where they came from. That's great.

The clarity of good video footage from 20 years ago is about the same as if it was shot yesterday. When I watched Nick-at-Night as a kid, the shows from 20 or 30 years before then were noticeably grainy. The colors were muted. Bright objects left brief streaks as the camera panned across views decorated with stuff you'd find in the dustiest antique stores today.

When I'd see an actor from one of those old shows in a present-day talk show interview or something, his being older did not phase me. The world I saw him inhabit as a younger man was a world that seemed far away. Looking through the grain, the washed out colors, the phosphene streaks, was like looking at a distant planet with a pair of binoculars on a humid night when the atmosphere shimmers and makes ripples that remind you what you're looking at is infinitely out of reach.Today, when I see something that was recorded 20 years ago, I don't see those people through the haze of the past's future breakthroughs in image fidelity. I see them 20 years younger now. The guy who's on the talk show on one station while reruns of his 20-year-old show plays on another is simultaneously old and young, simultaneously inhabiting a world that is older and younger. My view of both is the same.

I joined Instagram because someone I know who worked in publishing said it was where her company found an artist they hired. I joined in search of professional recognition, a form of vanity most condoned by the ravenous capitalism that acts as the substrate of our culture, but vanity nonetheless. And, like all vanity, its principal function is to act as a lever by which the unprepared are exploited.

I was unprepared. Something like two years later, I'm regularly laughing at 3am on animal videos by strangers and seeing how many people like my latest low-effort joke post.

The platform has rewarded me with some interactions with interesting and talented people, but I'm constantly reminded that it's the platform that's doing most of the rewarding, and less so the people with whom I'm interacting. This interaction was served to me, these connections undoubtedly tailored and recommended based on what it sees me posting and finds me looking at most as I scroll in the middle of the night, as I scroll first-thing in the morning.

No longer am I the travelling seller in search of a broader market. I'm not even the buyer. That would too quaint for the labyrinth of serotonin spikes created by overgrown tech-bros to contain and confound our restless imaginations. I am again the product, a quantifiable unit that can be conditioned to buy things and about which information can be gathered and sold to the real sellers.

Fortunately, it's not too late for any of us to escape this labyrinth, or at least learn how to better navigate it when we decide to.

For me, this means simply continuing to be aware of what I'm doing and to act more deliberately when it comes to spending time online. It's nothing revolutionary. Few useful things are.

About a month ago, I decided to go for a bike ride. Since it had been a while, I gave my bike a once over. This included spinning the wheels to see if there was any rubbing or resistance. There was, from the brakes. No problem, I thought. Just adjust the centering. It didn't work. A closer look at the turning wheel revealed a nasty wobble that would always cause brake rub until I learned how to true wheels. So, it was time to learn how to true wheels. I did, and it fixed the rub, but I couldn't stop there.

Last year I moved back home to be on hand for my family. This means I had a handful of old bikes to fix, a long road to drive this fascination along. I've been replacing rim tape, changing tires, lubing joints, degreasing chains and chainrings, taking apart and regreasing hubs, replacing cables and cable housings, cleaning bottom bracket shells and tightening up bottom brackets, and loving every minute of it, even the frustrating ones.

When I tried to do this stuff as a kid, I didn't have the resilience or patience to overcome the challenges of learning how to work on even simple technical systems like those in a bicycle. I wouldn't have been able to handle stripping bolts, crushing handlebars because I got the torque wrong, finding a new problem on my way to fix another.

These things are alright now. Maybe living a bit teaches you that this stuff is alright.

Instant access to YouTube tutorials and common torque specs from any room in the house is a big help too. Didn't have that when I was a kid. Just books. Gross.

In the future, everything from space ships to household lighting will hover. That's what our sci-fi would have us believe, anyway.

Space ships will still need giant thrusters to make them move forward, of course, and cars will still need big engines to make the wheels turn. But to simply overcome the bond between anything with mass and its nearest planet? That's nothing. Why wouldn't a landspeeder be able to soundlessly float a foot off the ground? Why wouldn't a mobile Chinese lunch counter be able to bob there quietly enough for the old cook to offer sage advice to a customer at the window of his 300th floor apartment-pod?

Despite the stereotypical sci-fi fan's habit of pointing out plot holes, inconsistencies, and tired tropes, inexplicable hovering is almost universally treated as a given, a near-necessity in any universe that takes place in the distant future or a galaxy far, far away.

I made the pencil drawing for this a couple of years back. I like to think this digitally inked version has the impact and immediacy that the original seemed to lack.

Space proselytizer, Inspired by the priest in Isaac Asimov's Foundation.

Weird business

Before the pandemic, I would walk each day to and from my job in an office building. One morning, as I approached it from the sidewalk on the other side of the parking lot, my attention drifted to two conversing figures in one of the office windows. Though they were on the first or second floor, I had to look up a bit to see them, as all of the offices in this building sat above three floors of garage.

Though these men were typical specimens of that environment, unremarkable of build and manner, each wore three strange articles of clothing.

As they spoke, a flexible band of material bobbed in front of each face. It was attached by a belt worn around the head. The bobbing part may have been the excess of the belt itself, left to dangle conspicuously in front of the wearer's face without any loops to secure it. They wore silver-gray suit jackets that didn't seem to go well with their pants. And atop each shoulder sat a pointy shoulder pad that looked like a cheap imitation of something out of an old sci-fi cover.

One of them pointed to a spot on the floor. They both looked as they kept talking.

I didn't ask anybody in the office about this for fear I'd sound crazy. I didn't investigate further for fear I'd learn something that two weirdly dressed office men would prefer I didn't know.

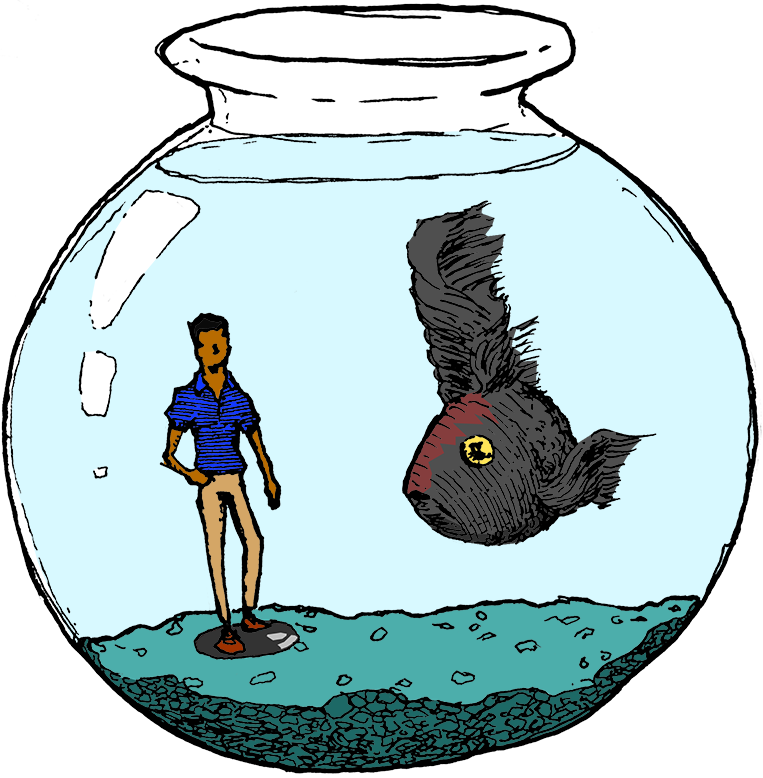

Near my home there's a shopping center with mostly "outlet" versions of designer stores. Interspersed among the Adidas, Aeropostales, Brooks Brothers, are less-premium but equally corporate franchises like "Go! Games and Toys" and the municipal police training center.

This shopping plaza is nearly identical to one that's a state over, owned by the same company, designed apparently by the same architecture firm, and imbued with a soul that was apparently manufactured in the same advertising agencies. The same faces smile above the same clothes in the windows.

Sophisticated people are supposed to lament the loss of culture and small business that these shopping centers are supposed to represent. Sophisticated people are supposed to prefer wood paneling instead of stucco. Sophisticated people are supposed to love the person who sells you things -- usually things you don't need -- when the person who owns the store lives in the same town as you. Maybe there's something to that.

I walk around there sometimes and enjoy myself. I'll buy a coffee from the Starbucks. I'll listen to the muzak and pretend to browse J Crew while I think about nothing. I'll tell the person working there that I'm just browsing when they ask if they can help me find anything. Then I'll start to feel like I may actually want to buy something.

The perpetually dry fountains and the gum on the sidewalk remind me that culture has nothing to do with anything in this fish bowl, and that culture has nothing to do with anything that a person can point to and call culture.

Thank goodness for my Tall coffee. The steam on my glasses and the green mermaid lady logo takes me back to my college days. Now there was a Starbucks that could make a scone. Those were the days.

A tree fell on the fence by the retention pond some time before March 3.

It looked kind of like this, but farther away.

A nearby resident was doing yard work. I didn't ask him about it.

I noticed more litter along the side of the road. Maybe it's because the cold has thinned the foliage that hid it. Maybe there's just more of it. I think I would have noticed the three piss bottles before.

Some of the litter is in people's back yards. Maybe they haven't thought to look back there while it's still too cold to mow.

In the big field of the church on the other side of the road, they set up German Shepherd-shaped cutouts to scare the geese away.

Sometimes I go running and sometimes I ride my bike. I like both and take neither seriously.

How you look around at stuff differs depending on whether you're riding or running. When you ride, your eyes dart around, scanning for obstacles, cars, curbs and driveway aprons to pop sick air off of. Everything you see is factored and evaluated. What you really take in is the cumulative experience of all this stuff zipping by.

When you run, you can really look at stuff. You can pick out some thing in the distance, think about some other thing it reminds you of, and then remember you've been staring at a telephone pole for a quarter mile as you pass it. Then on to the next thing, the next series of things.

In the free-to-play Bitburner, you use JavaScript to "hack" simulated servers. It takes place in a terminal-like environment, where you can write scripts. The better your scripts, the higher your score.

The network architecture and techniques are very pared down. For instance, a simple "hack()" command will siphon money out of an unprotected server into your account. This was a good game design choice. By abstracting some complicated tasks with built-in functions, the game encourages you to learn and practice the fundamentals: variables, loops, data structures, modules. It's all in there, and you can use real JavaScript on it.

You have a choice between two scripting languages. Netscript, which is like a simplified version of JavaScript, and NetScript2, which gives you access to all of the basic syntax and vocabulary of JavaScript.

It's a fun, addictive game that can actually turn out to be quite educational. It's important that it's not an educational game that happens to be fun. You don't read up on asynchronous functions because that's the name of some chapter or unit. You do it because you suspect it holds the key to why your script isn't doing what it's supposed to do. This motivates you to learn fast and immediately put things into practice.

My only complaint is that after a while, the scope of your goals seems a bit narrow. Find targets, siphon money, maybe figure out a more clever way to traverse the network. It gets a little monotonous after a while. It would be cool to apply your programming knowledge to a broader range of problems. Sure, you could just "do software development," solve real-world problems, and maybe even build a real-world career, but that's not a video game, so how could it be any fun on a Saturday evening?

But that’s realism, real realism. Ask anyone to draw a teapot in ten seconds, and they don’t do this. Even somebody who’s been drawing for years will give you a line drawing. Whenever somebody needs to efficiently convey the idea of a thing that can be pictured, they start with a line drawing. It seems to come naturally.

To understand these kinds of drawings also seems to come naturally. Nobody has to be taught that a line represents the boundary between a sudden change in the frequency of light waves from one part of a picture to another. Nobody has to be taught that the line isn’t actually there. Nobody’s ever said, "this is clearly a teapot, but why does it have what appears to be a timing belt along its outer edge?"

We seem to have some ingrained understanding of this type of drawing, which can be called realistic without actually looking anything like what it’s made to depict. So, to practice this type of drawing is not only to capture what you see. It’s to come closer to understanding what it means to see it, and what seeing something really tells you about it, about us.

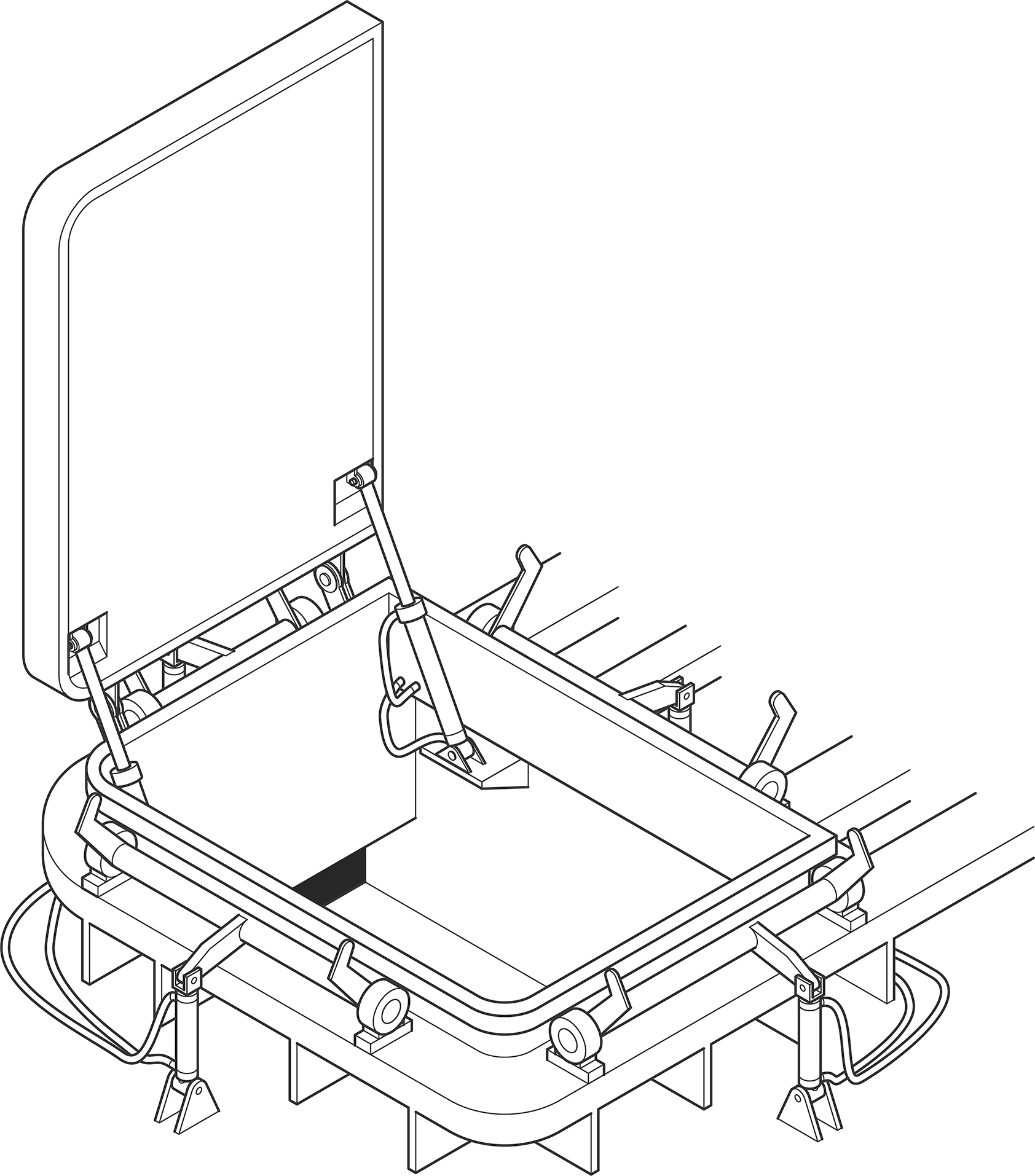

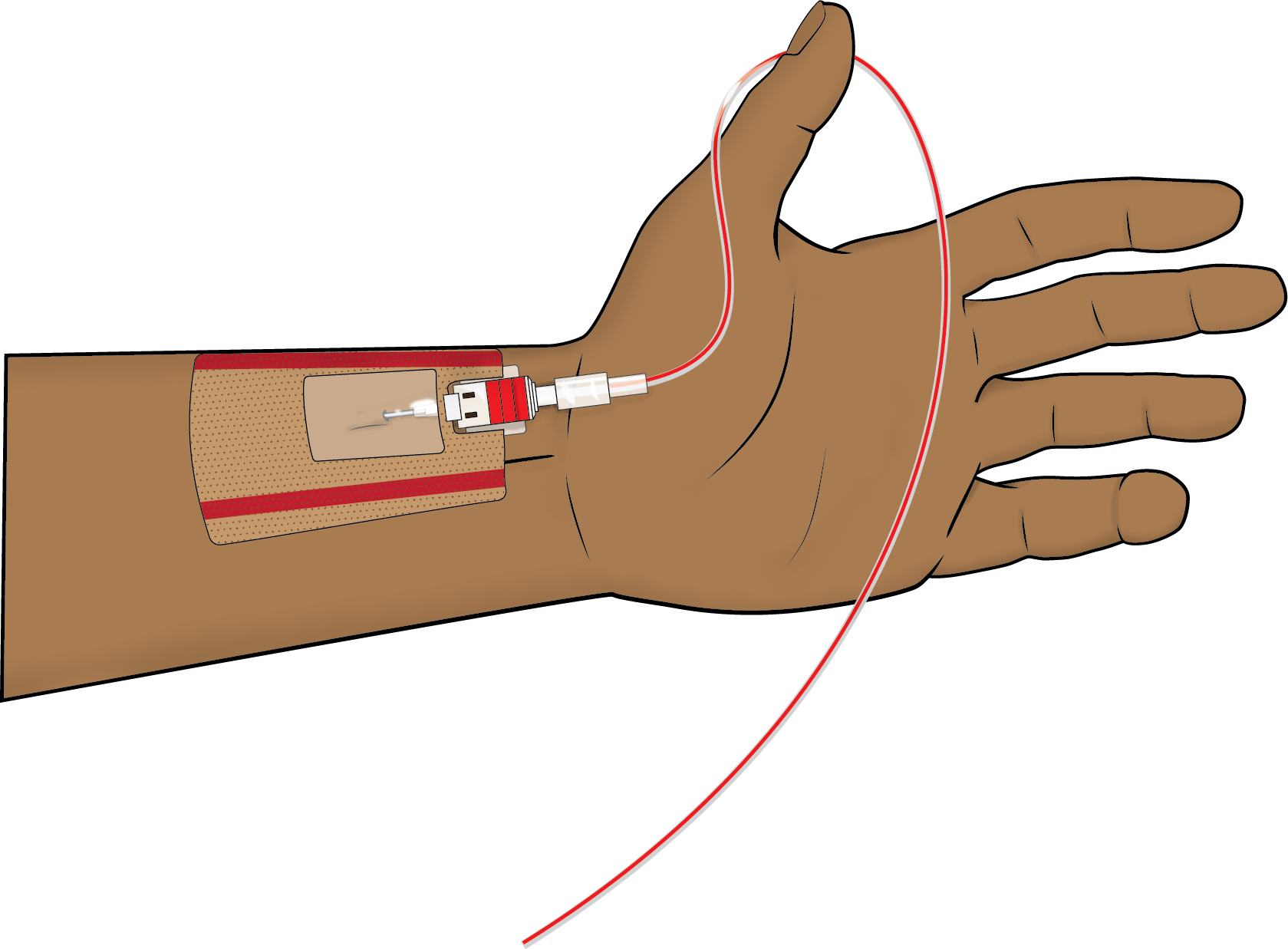

I've been trawling the Wikimedia Commons File Requests page for opportunities to help out with some technical illustrations for pages that could use them. It's been a great way to practice and learn new stuff. Here's a couple I made over the past week.

Wellboat hatches like this are common on the decks of big commercial fishing boats that carry live fish. This illustration is included in the Norwegian Wiki article for the MS «Rohav», one such wellboat. A worker on the Rohav was killed in 2018 when a failure in a hatch's hydraulic control system caused the lid to close on him.

This illustration was made for the Wikipedia article Arterial line, which previously only included pictures of the devices themselves.

2022 Feb. 5 - Added real responsiveness to the navigation links. Changed font throughout to Georgia because apparently Times New Roman is for plebs, which is actually a very good reason to use it. Maybe I'll change it back later. Added this change log.